What Did the Literature the Visual Arts and Music Portray About the Two World Wars?

During World War Two, the relations between art and war can be articulated around ii main problems. Start, art (and, more generally, civilisation) found itself at the middle of an ideological war. Second, during World War II, many artists constitute themselves in the most difficult atmospheric condition (in an occupied country, in internment camps, in expiry camps) and their works are a testimony to a powerful "urge to create." Such artistic impulse can exist interpreted every bit the expression of self-preservation, a survival instinct in critical times.

Historical context [edit]

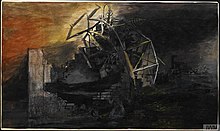

Throughout history, virtually representations of war draw war machine achievements and oft bear witness significant boxing scenes. However, in the 19th century a "plough" in the visual representation of state of war became noticeable. Artists started to show the disastrous aspects of war, instead of its glorified events and protagonists.[1] Such a perspective is best exemplified by Francisco Goya'southward series, The Disasters of War (1810-1820, first published in 1863), and Otto Dix's portfolio, Der Krieg (published in 1924).

During World State of war 2, both traditions are nowadays. For case, Paul Nash's Battle of Great britain (1941) represents a scene of aerial combat between British and German fighters over the English aqueduct. On the other hand, André Fougeron's Street of Paris (1943) focuses on the impact of war and occupation by armed forces on civilians.

Art in Nazi Germany [edit]

WWII art [edit]

In totalitarian regimes (especially in Hitler's Germany), the control of art and other cultural expressions was an integral function of the establishment of power. It reflects totalitarianism's aim to control every single aspect of society and the individuals' lives. Nevertheless, art and culture had a special importance because they have the power to influence people, and they embody the identity of a nation, a customs, a group of people.

In Nazi Germany, Hitler'due south cultural politic was twofold. The first pace was a "cultural cleansing". German culture and society were said to be in decline because forces of decadence had taken over and corrupted it (it is the idea of the "enemy inside").[ commendation needed ] The cultural cleansing was to be accompanied by a "rebirth" of German culture and lodge (Hitler had 1000 plans for several museums), which involved an exaltation of the "true spirit" of the German people in art.[ citation needed ] This officially sanctioned art was conservative and figurative, heavily inspired by Greco-Roman art. Information technology was often grandiose and sentimental. In terms of contents, this art should correspond and convey the regime's ideals.

In 1937 in Munich, two simultaneous events demonstrated the Nazis' views about art. One exhibition displayed art that should be eliminated ("The Degenerate Art Exhibition"), while the other promoted, by contrast, the official aesthetic ("The Smashing High german Art Exhibition").

In Europe, other totalitarian regimes adopted a similar opinion on art and encouraged or imposed an official artful, which was a form of Realism. Here Realism refers to a representational, mimetic style, and not to an art deprived of idealization. Such way was anchored in a prestigious tradition – pop, like shooting fish in a barrel to understand, and thus practical for propaganda aims.[ citation needed ]

It was clear in Stalin's Soviet Union, where diversity in the arts was proscribed and "Socialist Realism" was instituted as the official manner. Modernistic art was banned as being decadent, bourgeois and elitist.[ commendation needed ] The comparison of sculptures placed past national pavilions during the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris is revealing. The exhibition was dominated past the confrontation between Federal republic of germany and the Soviet Union, with their imposing pavilions facing each other.[ii] On one side, Josef Thorak'due south sculptures were displayed past the German language pavilion'south entrance. And on the other, Vera Mukhina'south sculpture, Worker and Kolkhoz Adult female, was placed on top of the Soviet pavilion.

Degenerate art [edit]

The term "degenerate" was used in connection with the idea that modernistic artists and their art were compromising the purity of the German race. They were presented every bit elements of "racial impurity," "parasites," causing a deterioration of German society.[ citation needed ] These decadent and "degenerate" forces had to exist eradicated. Cultural actors who were labelled "un-German" past the government were persecuted: they were fired from their instruction positions, artworks were removed from museums, books were burnt.[ commendation needed ] All artists who did not fall in line with the party'south ideology (to a higher place all Jewish and Communist artists) were "un-German." The Degenerate Art Exhibition (Munich, 19 July-30 Nov. 1937) was fabricated out of works confiscated in German language museums. The works were placed in unflattering ways, with derogatory comments and slogans painted effectually them ("Nature as seen past sick minds", "Deliberate sabotage of national defense"...). The aim was to convince visitors that mod art was an attack on the High german people. Mostly, these works of fine art were Expressionist, abstract or fabricated by Jewish and Leftist artists. The exhibition was displayed in several German and Austrian cities. Subsequently, most of the artworks were either destroyed or sold.

Modern fine art could non autumn in line with the Nazi values and taste for several reasons:

- its constant innovation and alter

- its independency and liberty

- its cosmopolitanism and reticence to profess whatsoever type of nationalist fidelity

- its ambiguity and its lack of easily understandable and definitive meaning

- its rejection and deconstruction of the mimetic tradition of representation[ citation needed ]

France was occupied by Nazi Frg from 22 June 1940 until early May 1945. An occupying power endeavours to normalise life as far as is possible since this optimises the maintenance of social club and minimises the costs of occupation. The Germans decreed that life, including artistic life should resume equally before (the war). At that place were exceptions. Jews were targeted, and their art collections confiscated. Some of this consisted of mod, degenerate fine art which was partly destroyed, although some was sold on the international art marketplace. Masterpieces of European art were taken from these collectors and French museums and were sent to Frg.[three] Known political opponents were also excluded and overtly political fine art was forbidden.

Persecuted artists [edit]

During the rise of Nazism, some artists had expressed their opposition. After the Nazis seized power, modern artists and those of Jewish ancestry were classed as degenerate. Any Jewish artists, or artists who were known opponents to the authorities, were liable to imprisonment unless they conformed with the authorities' view of what was "acceptable" in art. These artists were all in danger. Among those who chose to stay in Deutschland, some retreated into an "inner exile", or "inner emigration"[4] ("Innere Emigration").

Artists had the choice of collaborating or resisting. But most people in such a predicament will normally find a middle way. Resistance was dangerous and unlikely to escape fierce penalty and while collaboration offered an easier path principled objection to it was a strong deterrent to many if not most. The other options were withdrawal, finding refuge abroad or, for many, to take the businesslike course by but continuing to work within the new restrictions. Hence artistic life and expression appeared calorie-free, carefree and frivolous, but was likewise lively.[5]

Exiled artists [edit]

v Fingers Has The Paw by John Heartfield, 1928

The German language creative person John Heartfield (who had been part of Dada Berlin) is an example of an artist who expressed opposition. While Hitler'southward popularity was growing in Germany, he consistently produced photomontages that denounced the future dictator and his party. Nearly of them were published in Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung [AIZ, Workers' Illustrated Newspaper], and a lot of them appeared on the cover. His artworks were like visual weapons against Nazism, a counter-power. In them, he subverted Hitler'southward figure and Nazi symbols. Through powerful visual juxtapositions, he revealed Nazism manipulations and contradictions, and showed the truth almost them. Every bit soon every bit Hitler came to power in 1933, Heartfield had to flee, finding refuge first in Prague and then in the UK.[ citation needed ]

Otto Dix had been labelled as a "degenerate" artist. His works were removed from museums, he was fired from his teaching position, and he was forbidden to create anything political besides every bit to showroom. He moved to the countryside and painted landscapes for the duration of the war.[ citation needed ]

Many artists chose to exit Germany. But their exile did not secure their position in the art world abroad. Their personal and artistic security depended on the laws and attitude of the land of exile. Some sought collaboration with others in exile, forming groups to exhibit, such as the Gratuitous High german League of Culture founded in 1938 in London.[vi] Ane of their goals was to testify that German language culture and art were not to be equated with the cultural expressions sanctioned and produced past the Nazi authorities.

Other artists went their ain way, independently, often choosing apolitical subjects and sometimes refusing to participate in political events.[seven] They considered art as a completely democratic activity that should non be submitted to a political cause. On the contrary, someone similar Oskar Kokoschka, who had until then rejected the idea that art should be useful and serve a cause, got involved in these groups when he emigrated to London in 1938. He created a series of political allegories, i.e. paintings in which he made comments on state of war politics.[8]

Artists in internment camps [edit]

In one case the state of war had commenced, anybody of Austro-German extraction was considered to be a security risk in Britain and became an enemy alien. They were interned in 1940, in camps on the Isle of Man. In United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, notwithstanding, at that place was considerable concern that many who had opposed the Nazi authorities and escaped with their lives were now in detention in poor conditions. This led to a grade of re-classification that led to many early releases in 1940, and past 1942 well-nigh of the internees had been released.[ citation needed ]

Within the camps, some of the inmates were artists, musicians, and other intelligentsia, and they rebuilt every bit much cultural life as they could within the constraints of their imprisonment: the giving of lectures and concerts and the creation of artworks from materials like charcoal from burnt twigs, dyes from plants and the use of lino and paper. They besides received materials from the creative community in Great britain.[ citation needed ]

Heinz Kiwitz went into exile in 1937 afterwards his release from imprisonment in Kemna and Börgermoor concentration camps. Max Ernst exiled to the United States in 1941.[ commendation needed ]

In French republic, Austro-High german citizens as well became "enemy aliens" at the outbreak of state of war and were sent in internment camps. The Camp des Milles, near Aix-en-Provence, where High german artists such as Max Ernst and Hans Bellmer were imprisoned, was famous for its artistic life.[ citation needed ] Every bit France was invaded, the situation of exiled German artists got more than complicated and dangerous. They risked displacement, forced labour and extermination in the case of Jewish artists, both in occupied France and in the Vichy Republic. Most chose to emigrate further while others went into hiding.[ citation needed ]

In the The states, citizens of Japanese extraction also faced internment in very poor living conditions and with trivial sympathy for their plight throughout the period of hostilities and beyond.

Globe War II art [edit]

Protest fine art [edit]

Those who wished to overtly oppose the Nazis in their art either worked away (for instance, André Masson) or clandestinely, as part of the resistance movement (such as André Fougeron). In the public space, resistance took on more symbolic forms. A grouping known equally 'Jeunes peintres de tradition française' exhibited in Paris for the showtime fourth dimension in 1941. The works they produced during the period were characterised by semi-abstract art and bright colours, which they considered as a form of resistance to the Nazis.[ix] Other supposedly non-political works were ambiguous – they observed the hardships of life in French republic without apportioning blame. Picasso, who had stayed in Paris, painted but refused to showroom. He did non paint the war or anything openly political, but he said that the state of war was in his pictures.[10]

Modern art became the bearer of liberal values, as opposed to the reactionary creative preferences of the totalitarian regimes. Artistic choices embodied different positions in the ongoing ideological battle. Placing Alberto Sánchez Pérez'southward abstract sculpture,[11] The Spanish people have a path that leads to a star (1937), at the entrance of the pavilion of the Spanish Republic was a political statement. So was commissioning modernistic artists to create works of fine art for this pavilion. Pablo Picasso showed 2 works: a pair of etchings entitled The Dream and Lie of Franco, 1937, and his monumental painting, Guernica, 1937. Joan Miró painted a huge landscape entitled Catalan Peasant in Defection (aka The Reaper, destroyed), and he did a affiche entitled "Aidez 50'Espagne" (Help Espana), meant to support the Republicans' cause. The American creative person Alexander Calder created the abstract sculpture Mercury Fountain (1937). The involvement of a non-Spanish artist was also an important statement in an era dominated by the ascent of nationalism, both in democratic and totalitarian regimes.

Even in democracies, voices called for a return to a more representational style. For instance, some criticized the central place given to Picasso'south Guernica considering it was not explicit plenty in its denunciation and was too complex.[12] They would have preferred that the focus be placed on paintings such as Horacio Ferrer'south Madrid 1937 (Black Planes), from 1937. Its "message" was much clearer and – as a event – it functioned better as a political statement.

When they wanted to back up the democratic crusade and protest against Fascism and dictators, artists were ofttimes encouraged to put aside their modernist way and express themselves in a more realist (i.eastward. representational) style. For instance, Josep Renau, the Republican Government'south director general of Fine Arts, said in 1937: "The poster maker, every bit an artist, knows a disciplined freedom, a freedom conditioned by objective demands, external to his individual will. Thus for the affiche artist the elementary question of expressing his own sensibility and emotion is neither legitimate nor practically realizable, if not in the service of an objective goal.[13]" And the French author, Louis Aragon, declared in 1936: "For artists as for every person who feels similar a spokesperson for a new humanity, the Spanish flames and blood put Realism on the agenda.[14]" In other words, the artist'southward political date required a submission of the piece of work's creative aspects to the expression of the political content.

The series The Twelvemonth of Peril, created in 1942 by the American artist Thomas Hart Benton, illustrates how the boundary betwixt art and propaganda tin be blurred by such a stance. Produced as a reaction to the bombing of Pearl Harbor past the Japanese army in 1941, the series portrayed the threat posed to the U.S. past Nazism and Fascism in an expressive but representational mode. The bulletin is clearly and powerfully delivered. These images were massively reproduced and disseminated in order to contribute to enhance support for the U.S. involvement in Earth State of war Ii.[ citation needed ]

Thus, there can exist troubling affinities betwixt Centrolineal politically-engaged fine art and fascist and totalitarian art when in both cases fine art and artists are used to create "persuasive images", i.e. visual propaganda. Such a conception of political fine art was problematic for many modernistic artists as modernism was precisely defined by its autonomy from anything non-creative. For some, absolute artistic freedom – and thus freedom from the requirement of having a clear, stable, and easily decipherable meaning – should have been what symbolised the liberal and progressive values and spirit of democracies.[15]

Political fine art [edit]

Shelter Experiments, near Woburn, Bedfordshire by John Piper, 1943

Britain was also subject field to political differences during the 1930s but did not suffer repression nor civil state of war as elsewhere, and could enter World War II with a justifiable sense of defending freedom and commonwealth. Fine art had similarly followed the costless expression at the centre of modernism, but political cribbing was already sought [as in the left-wing Artists' International Association founded in 1933]. With the outbreak of war came official recognition of art'south utilize every bit propaganda. Withal, in U.k., political promotion did not include the persecution of artistic freedom in general.[ commendation needed ]

In 1939, the State of war Artists Informational Committee (WAAC) was founded under the aegis of the British Ministry of Information, with the remit to list and select artists qualified to record the war and pursue other war purposes. Artists were thought to have special skills useful to a country at war: they could translate and express the essence of wartime experiences and create images that promoted the country's culture and values. Non the least of these was artists' freedom to choose the subjects and style of their art.[ citation needed ] A meaning influence was the choice of Sir Kenneth Clark as instigator and director of WAAC, every bit he believed that the beginning duty of an artist was to produce skilful works of art that would bring international renown. And he believed the second duty was to produce images through which a country presents itself to the earth, and a tape of state of war more expressive than a camera may give.[ citation needed ] Of import to this was the exhibition of Britain at War at Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1941 (22 May to 2 September).[ citation needed ]

This initiative also provided support for British artists when the world seemed to exist sinking into atrocity. Just it was non without intentions and constraints, and some works were rejected or censored. Accurate representations were required and abstract art, as it did not deliver a clear message, was avoided. Some depictions could be too realistic and were censored because they revealed sensitive information or would have scared people – and maintaining the nation's morale was vital. No foreign artists were admitted to the programme, a great sorrow to many who had fled to Britain from persecution elsewhere.[ commendation needed ]

Despite these restrictions, the work deputed was illustrative, non-bombastic, and oftentimes of great distinction thanks to established artists such equally Paul Nash, John Piper, Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and Stanley Spencer.

Holocaust art [edit]

Many works of art and images were created by detainees in ghettos and in concentration and extermination camps. They form a large body of images. Nigh of them were minor and fragile, many were destroyed and lost. The large bulk of these images were created clandestinely considering such a artistic activity was frequently forbidden and could have resulted in a death penalty. Yet, many inmates found materials and transgressed the rules in order to create.[ commendation needed ]

Their motives for doing so were multiple only they all seem to take been linked to a survival instinct and self-preservation.[sixteen] Art could exist a distraction and an escape from the horrors of the present. Distancing oneself (by depicting imaginary scenes or by taking on the function of the observer) was a manner to keep some sanity. Doing drawings could likewise be a way to barter and thus to increase one's chances of survival in the camp or ghetto. Moreover, by creating visual artefacts there was the hope of creating something that would survive to 1's death and would live on to bear witness to one's existence. Some seemed to have been animated past a documentary spirit: recording what was happening to them for people beyond the fence. Finally, such a creative urge was a course of cultural resistance. When their persecutors were trying to eradicate every bit of their humanity, artistic cosmos and testimony were ways to reclaim it, to preserve and cultivate information technology.[ citation needed ]

In terms of field of study matters, the images created in concentration and extermination camps are characterised by their determination to enhance the detainees' dignity and individuality.[17] This is probably the most visible in the numerous portraits that were washed. Whereas the Nazi extermination machine aimed at dehumanising the internees, creating "faceless" beings, undercover artists would give them back their individuality. In this body of works, depictions of atrocities are not and so frequent, which suggests that they might have been intentionally avoided. Rather, it is later the liberation, in the art of survivors that the well-nigh brutal and abominable aspects of concentration and extermination camps found a visual expression.[ citation needed ]

In the face of such horrors, some artists were confronted with ethical issues and felt that representation had reached a limit. Thus, since the liberation of the camps, artists who accept wanted to express the Holocaust in their fine art have often chosen abstraction or symbolism, thus avoided any explicit representations. A few went as far as to suggest that art itself – and not simply representational art – had reached a limit because creating an aesthetic object near the Holocaust would exist, in itself, unethical, morally reprehensible.[xviii]

References [edit]

- ^ Laurence Bertrand-Dorléac (ed.), Les désastres de la guerre, 1800-2014, exh. cat., Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, Somogy, 2014 ; Laura Brandon, Art and War, London: IB Tauris, 2007, p. 26-35

- ^ Dawn Adès (et al.), Art and Power: Europe under the Dictators, 1930-1945, London: The Due south Depository financial institution Centre, 1995

- ^ Lionel Richard, L'art et la guerre: Les artistes confrontés à la Seconde guerre mondiale, Paris, Flammarion, 1995, chapter five, « Butins de guerre » ; Laurence Bertand-Dorléac, Art of the Defeat. France 1940-1944, transl. from French past Jane Mary Todd, Getty Research Constitute, 2008, p. 12 and following

- ^ Lionel Richard, Le nazisme et la culture, éditions Complexe, 2006, p. 133

- ^ Cf. Alan Riding, And the Evidence Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris, Alfred A. Knopf, 2010; Laurence Bertand-Dorléac, Art of the Defeat. French republic 1940-1944, transl. from French by Jane Mary Todd, Getty Research Institute, 2008

- ^ "Arts in Exile", virtual exhibition, the German Exile Archive 1933-1945 of the German National Library, 2012: http://kuenste-im-exil.de/KIE/Content/EN/Topics/freier-deutscher-kulturbund-gro%C3%9Fbritannien-en.html (last retrieved: 04-04-2015)

- ^ Stéphanie Barron (ed.), Exiles + Emigrés, The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, exh. cat., Los Angeles Canton Museum of Fine art; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997

- ^ Cf. Stéphanie Barron (ed.), Exiles + Emigrés, The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, exh. cat., Los Angeles Canton Museum of Fine art, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997; Melody A. Maxted, "Envisioning Kokoschka: Considering the Creative person'south Political Allegories, 1939-1954", in Montage, 2 (2008): 87-97

- ^ Lionel Richard, 50'art et la guerre: Les artistes confrontés à la Seconde guerre mondiale, Paris, Flammarion, 1995, p. 190

- ^ Picasso, in Peter D. Whitney, "Picasso is Rubber", San Francisco Chronicle, 3 Sept. 1944, quoted by M. Bohm-Duchen, Art and the Second Earth State of war, Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013, p. 112

- ^ See Dawn Ades (et al.), Fine art and Ability: Europe under the Dictators, 1930-1945, London: The South Bank Centre, 1995

- ^ Monica Bohm-Duchen, Art and the Second World State of war, Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013, p. 25. Robin A. Greeley, Surrealism and the Castilian Civil War, New Haven: Yale Academy Printing, 2006, p. 241

- ^ Josep Renau, quoted by M. Bohm-Duchen, Art and the Second World War, Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013, p. 18

- ^ Louis Aragon, in La Commune, 1936, quoted by Lionel Richard, Fifty'art et la guerre: Les artistes confrontés à la Seconde guerre mondiale, Paris, Flammarion, 1995 (transl. from French)

- ^ K. Bohm-Duchen, Art and the Second World War, Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013, p. 87

- ^ Lionel Richard, Fifty'art et la guerre: Les artistes confrontés à la Seconde guerre mondiale, Paris, Flammarion, 1995, p. 216: for some internees, art had a « live-saving office » (transl. from French)

- ^ M. Bohm-Duchen, Art and the 2nd Earth War, Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013, p. 196

- ^ M. Bohm-Duchen, Art and the Second World War, Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013, p. 211

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_and_World_War_II

0 Response to "What Did the Literature the Visual Arts and Music Portray About the Two World Wars?"

Post a Comment